Staring at a page of a Pokemon book, Sawyer shakes and lifts his arms and legs, and waves his hands excitedly, appearing as if he’s break dancing. If he could, he would continue poring over the book for most of the day - never eating, drinking or moving from that one spot in the living room.

“Sawyer, one more minute and then we have to put the book away, OK?” his aide, Bridget says.

“Yeah.’’ His gaze stays on the page featuring one of the countless Pokemon characters - all of whose name and characteristics he’s memorized.

When a minute or so is up, Bridget gently reaches for his hands as she tries to guide him back to the other side of the living room, back to the exercise they had been working on. What is the opposite of... What color is... What shape is...

The first word Sawyer spoke was “robot.’’ A robot was on television and another was in a book he had seen. He was 19 months old and had made only cooing sounds before that. Sawyer’s parents were dumbfounded that he could make those connections and could actually speak.

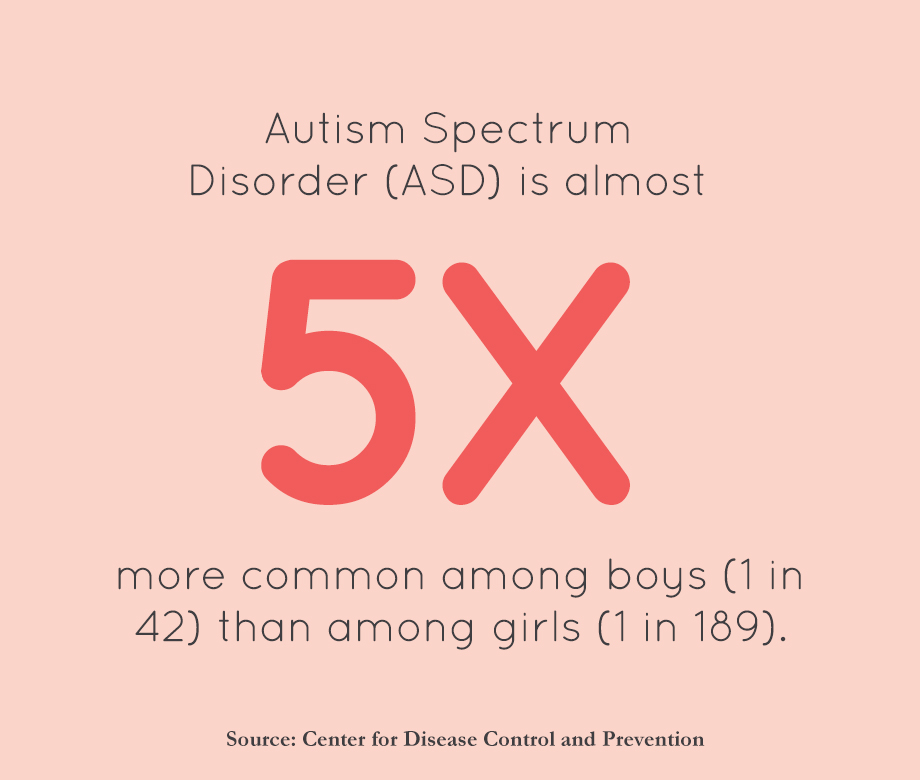

At a little over age 2, Sawyer was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. He is 7 now and works with an aide in his Bexley home several hours a week after school where he’s accompanied by a different aide. He and his aide work on identifying words and other skills. He practices responding to people who talk to him and calming his occasional urges to flail his arms and legs or cry when he’s frustrated.

Sawyer’s parents, Amy and Eric, focus on the progress they have seen in Sawyer in recent years, in part because of the teachers, therapists and aides he works with, in part because they have learned how to best support Sawyer. He has learned to speak in full sentences, have conversations and look up and respond when someone calls his name. Not so long ago, when asked to stop looking at a book, Sawyer would often scream, cry and sometimes drop to the floor. That seldom happens now.

“The world isn’t going to change for him,’’ Amy points out. “The people at Nationwide Children’s Hospital are giving him tools for better surviving and thriving in the world.”

Sawyer is working on better handling his anger and frustration by stepping out of the room or taking a deep breath instead of crying and being defiant. And he’s learning to say what is bothering him rather than leave people guessing. Recently a classmate pushed him. “Leave me alone,” Sawyer told him. That was a major feat.

From time to time, Sawyer will play with other kids at school, if only briefly, such as a game of tag. He used to turn his back on a group of kids, perfectly content to be alone.

In the corner of the living room, Sawyer asks Bridget: “Where is the Pokemon book?’’

His mom holds it up. When he comes to the table and opens it up to the picture and description of a character, his mother asks him to name the character. He says: Dragonaire, a blue and white snake-like figure.

“He evolves,’’ Sawyer says and starts up his dance again, arms and legs flapping.

Are you or someone you know in need of help?

View Community Resources